Following Norway’s announcement that it’s opening up new grounds for oil exploration, legal action brought by Greenpeace and Norway’s Nature and Youth organization argues that Oslo needs to keep Barents Sea oil in the ground.

A coalition of environmental and community activist groups filed a lawsuit last week against the Norwegian government over its decision to allow oil exploration in the Barents Sea.

In the lawsuit, Greenpeace Nordic and Natur og Ungdom (Nature and Youth, Norway’s largest youth environmental organization) asked the Oslo District Court to reverse the licenses distributed by the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy in May. They allege that the decision violates Norway’s constitution and compromises the success of the Paris climate agreement.

Here’s a short primer on the case:

What’s at stake?

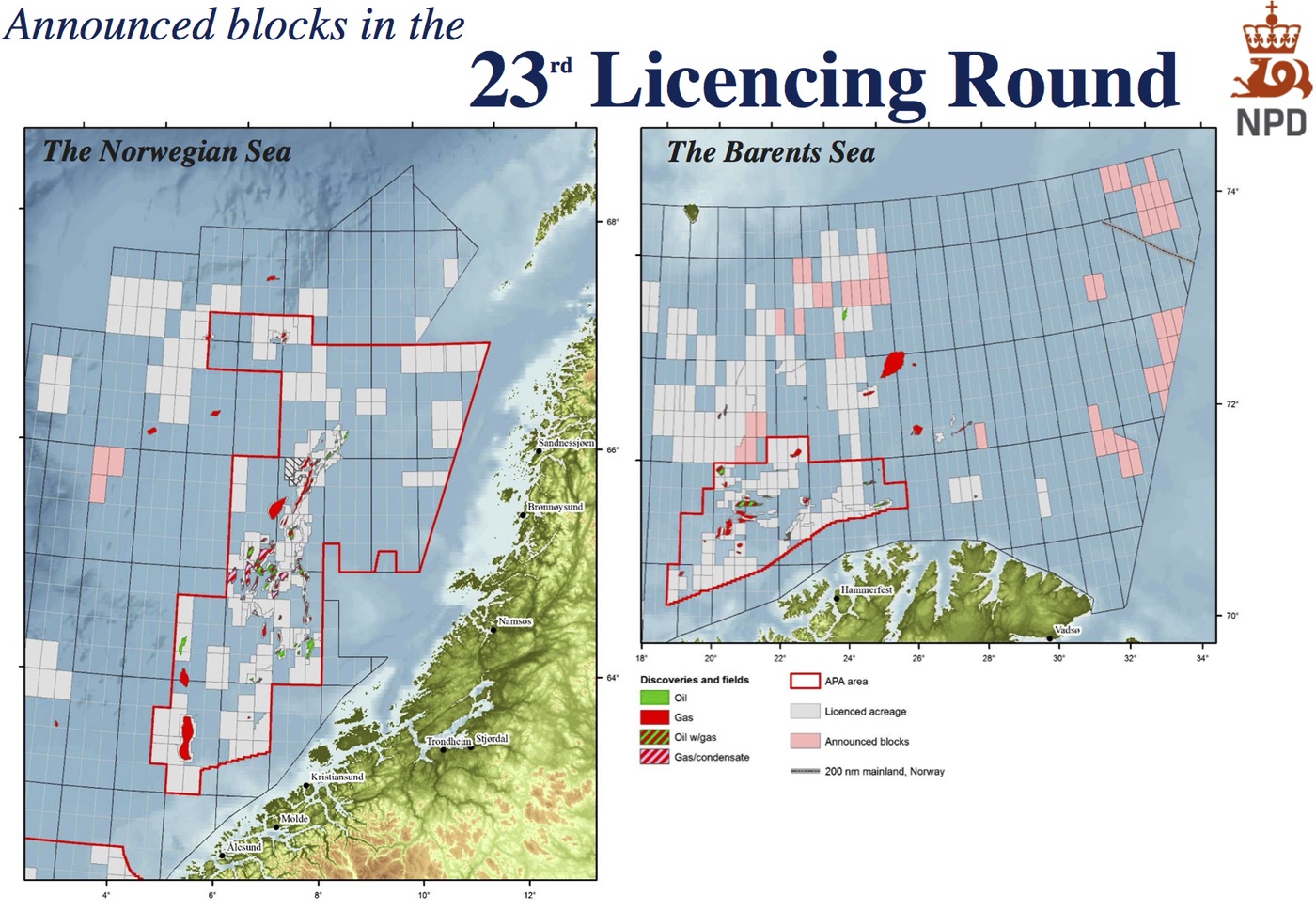

In January 2015, Norway’s minister of petroleum and energy Tord Lien announced the 23rd licensing round. It was the first time since 1994 that Norway had opened up new grounds for oil exploration. The map showed eight blocks north of the 74th parallel, on the far northeast edge of Norway – the southwestern corner of the Barents Sea.

“These are areas which are hitherto unexplored. This could open up a new petroleum province in the Barents Sea,” Lien said at the time. Discoveries elsewhere in the Barents Sea had hinted that these regions might also contain oil. According to a 2013 estimate, the Barents Sea might hold as much as 8 billion barrels of undiscovered resources. Norway’s oil output has halved since its peak in 2000.

The announcement had been delayed due to a quarrel over the location of the sea-ice edge. Norway passed a bill that bans drilling within 50 kilometers (30 miles) of the location where ice can be found from December 15 to June 15, due to the sensitivity of the ecosystem the sea ice supports.

At the time of the announcement, the environmental NGO Bellona, called the 23rd license round “a disaster for the environment.”

The lawsuit has been brewing for a long time

Environmental NGOs and lawyers have been hinting at legal action for well over a year. Truls Gulowsen, the director of Greenpeace Norway, published an editorial in October 2015 in the Norwegian newspaper Dagbladet, along with several legal experts, questioning the decision to include the Barents Sea blocks in the 23rd licensing round.

In December 2015, in the wake of the Paris agreement, Norwegian environmentalists issued calls for the government to halt further offshore oil and gas exploration, including the cancellation of the 23rd licensing round.

In January this year, two Norwegian lawyers published a paper in which they argued that under international law, E.U. law and the constitution, “exploiting oil and gas on the large scale in the Arctic is unlawful.”

Greenpeace sent a letter to the Norwegian government earlier this year outlining why the organization believes the licenses are unconstitutional and are in contravention of international law. “We have not yet received a response that is satisfactory,” Michelle Jonker-Argueta, legal counsel for Greenpeace International, said in mid-October.

The legal challenge hinges on two key arguments

The plaintiffs in the case, Greenpeace Nordic and Nature and Youth, make two key arguments in their legal challenge, which the Oslo district court must now reflect upon:

Norwegians have the right to a healthy and safe environment.

The lawsuit demands that the government uphold the guarantees contained in Article 112 of Norway’s constitution, a point that was amended two years ago and that grants Norwegians the right to a healthy and safe environment.

“Every person has the right to an environment that is conducive to health and to a natural environment whose productivity and diversity are maintained. Natural resources shall be managed on the basis of comprehensive long-term considerations which will safeguard this right for future generations as well. The authorities of the state shall take measures for the implementation of these principles.”

The Norwegian oil and gas ministry issued a statement that said that awarding the new licenses was not unconstitutional and that it was done according to law.

Norway ratified the Paris agreement.

At the Arctic Circle Assembly in Reykjavik, Iceland, in October, Jonker-Argueta argued that by ratifying the Paris agreement, Norway is expected to act in “good faith.”

“It is a treaty, and it has binding force on the parties,” she said.

Norway signed the Paris agreement in April, awarded the licenses in May, and ratified the agreement in June. Under the agreement, Norway has promised to reduce its emissions by at least 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030, its contribution toward the goal of holding global warming to 1.5C (2.7F).

Opening the wells would add a surplus of oil and gas to the market. “By issuing new production licenses in previously untouched areas, Norway will continue to contribute to major greenhouse gas emissions and thus exacerbate global warming,” reads the lawsuit, which has been translated to English and made available online.

Are there sticking points?

Yes. The sea ice edge has been retreating. The ice location between 1984-2013 is 60 to 70 kilometers (40-45 miles) north of where it was between 1969 and 1989, Reuters reported in 2015. According to the government, the shift suggests that the risks associated with drilling in the Arctic have been pushed northward.

On top of that, Norway consumes very little of the oil it produces. Most of the oil extracted in Norway is exported to Europe, including the Netherlands, United Kingdom and Germany, meaning that the oil is burned elsewhere and shows up on other countries’ carbon accounts.

On the other hand, Norway has a tradition of applying the precautionary principle. “We know there is sufficient risk of serious or irreversible harm,” said Jonker-Argueta. If the government were to try to argue that oil development in the region wasn’t risky, it would have to prove it, she said.

The Oslo District Court will decide whether or not it will hear the case. Jonker-Argueta said that Greenpeace is preparing to go to court by next summer.

This article originally appeared on Arctic Deeply.