This year saw record-setting Arctic temperatures and the continued shrinking of sea ice – and, perhaps most concerning, the warming trend is now being felt in the winter, too, as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration end-of-year report confirms.

The Arctic broke records for warm temperatures, shrinking sea ice and low snow cover in 2016, according to a new U.S. federal report.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) released its 11th annual Arctic report card on Tuesday, and the findings paint a dramatic picture of a rapidly changing region.

“We’ve seen a year in 2016 in the Arctic like we’ve never seen before,” said Jeremy Mathis, the director of NOAA’s Arctic research program, during a news conference on Tuesday.

Here are five major takeaways from this year’s report:

Temperatures Are Rising, and Rising Fast

The average air temperature over land in the Arctic between October 2015 and September 2016 was “by far the highest in the observational record beginning in 1900,” according to the new report. That temperature has increased by 3.5C (6.3F) since the turn of the 20th century, and continues to rise twice as fast as global temperatures.

Record temperatures were observed in January, February, October and November.

“The report card this year clearly shows a stronger and more pronounced signal of persistent warming than in any previous year in our observational record,” Mathis said.

Major Changes Are Happening in the Winter

To Mathis, what stands out about 2016 is that warming trends typical in the summer months are now being seen in the winter, too.

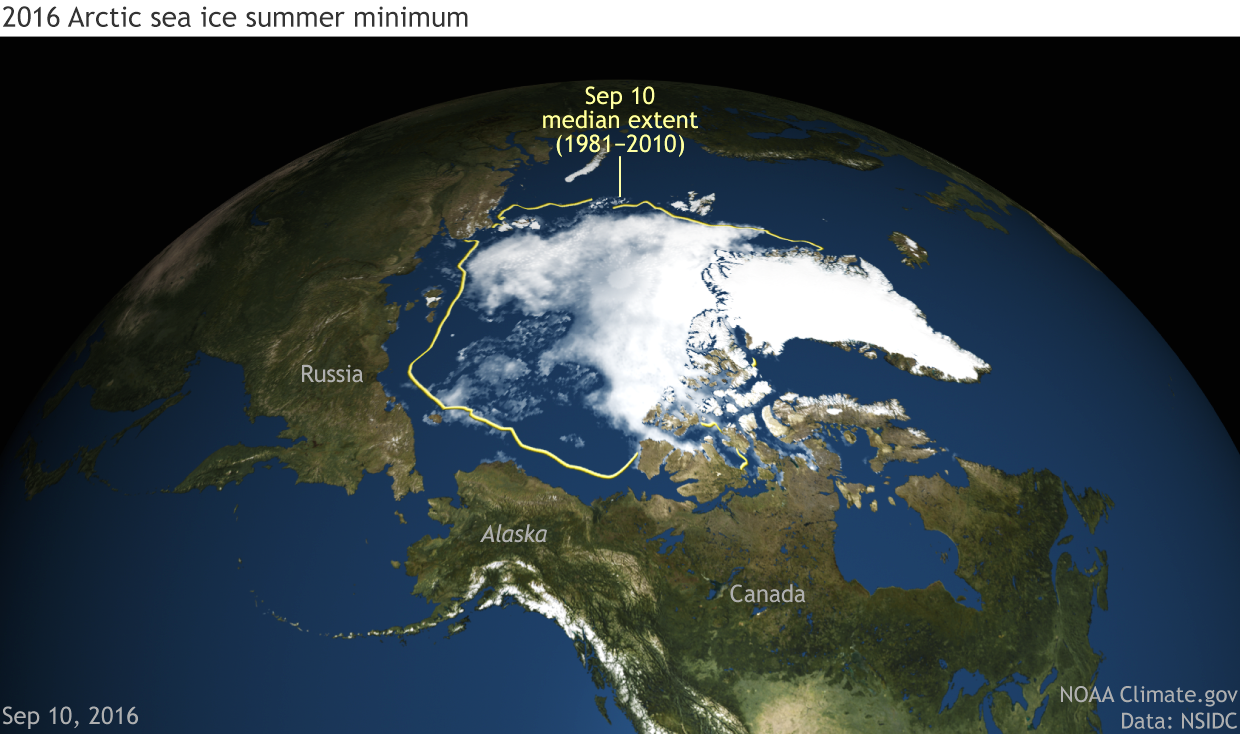

For instance, Arctic sea ice has been slow to regrow this fall. Sea ice extent from mid-October to late November was the lowest since the satellite record began in 1979, prompting Dartmouth College professor Donald Perovich, lead author on the report’s sea ice chapter, to give Arctic sea ice a grade of D+ this year, compared to B- 11 years ago. He said that in the 1980s, September sea ice was about the size of the continental United States. In 2016, he said, it’s as if all of the states east of the Mississippi and several others had melted.

“The Arctic was whispering change, and now it’s not whispering anymore,” he said. “It’s speaking change. It’s shouting change.”

Sea ice is also getting thinner as it recedes. In March 2016, 78 percent of Arctic sea ice was first-year ice, which is much thinner than the multi-year ice that builds up over time. In 1985, just 55 percent of sea ice was first-year ice.

Snow cover in the North American Arctic also set a record low last April and May, when it dropped below 4 million square km (1.5 million square miles) for the first time since 1967.

Mathis said those wintertime changes are worrying, because the winter months usually allow the region to “reset” after warmer summers.

“It was one thing for warm to get warmer, but it’s a completely different thing if the cold were to start getting warmer,” he said.

Mathis said the recent El Nino event, one of the strongest on record, likely affected conditions in the Arctic this year. But he said researchers aren’t yet able to quantify that impact.

“We’ll be working on that in the coming year.”

Algae Blooms Are Becoming Widespread, Raising Concerns About Acidification

Shrinking sea ice allows more light to reach the surface of the Arctic Ocean, which stimulates the growth of algae and other tiny marine plants at the base of the food chain.

In itself, that’s not necessarily a bad thing, Mathis explained in an interview with Arctic Deeply. “That would provide greater food sources to the ecosystem in the Arctic,” he said.

But more growth means the ocean will likely take up even more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, which causes ocean acidification. And the Arctic Ocean is already prone to acidification because of cooler water temperatures and the melting of sea ice.

The Tundra Is Changing, Too

Arctic climate change isn’t restricted to the ocean. Warmer temperatures are also causing permafrost to melt, which releases carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere.

“There is a very large potential amount of carbon that could be released from those soils if this warming trend continues,” Mathis said.

Much of the tundra is also greening over time, suggesting there’s more vegetation growing in the Arctic. That could account for the fact that the tundra is absorbing more carbon during the summer than it used to. But throughout the year, tundra ecosystems seem to be releasing more carbon than they’re taking up.

Southern Critters Are Moving North

This year’s report card shows that some Arctic shrews have acquired new parasites, suggesting that sub-Arctic species are moving northward. Mathis said the shrews are a “great test study,” but the results show that researchers need to focus on how the warming Arctic is affecting larger wildlife as well, including caribou.

In fact, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada concluded earlier this month that barren-ground caribou stretching across the Canadian Arctic should be considered threatened due to rapid population declines in most of the major herds.

In Short: What This ‘Bellwether Year’ Means for the Arctic

Overall, Mathis said, 2016 was a “bellwether year for Arctic change.” He believes the warming Arctic could have impacts on weather patterns, food security, resource development and national security in the North, as ice clears from northern transportation routes.

For Arctic communities, he said, the changes present both challenges and opportunities.

“I think they should be concerned, because it’s getting harder and harder for them to harvest resources as the ice pulls back further and further away from the coast,” he said during the news conference.

But the changes will also create new possibilities for resource development, tourism and shipping, he continued.

“We just have to make sure … that no one gets left behind as the Arctic transitions.”

This article originally appeared on Arctic Deeply.