RESIDENTS OF NUNAVUT in Canada’s eastern Arctic are accustomed to slow, spotty and expensive internet service. Their territory is the only Canadian jurisdiction that still entirely relies on internet connections offered by satellite links due to a lack of any fiber-optic internet connection.

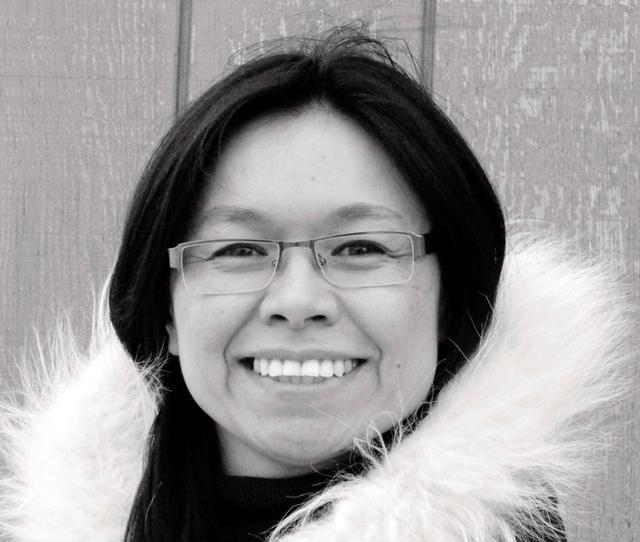

This state of affairs is stifling economic development and government operations, says Madeleine Redfern, the mayor of Nunavut’s capital, Iqaluit. Redfern says that when the internet cuts out, which is common, it interferes with daily life and every level of government. Transferring big files can be so slow and expensive that government workers have been known to move data by putting it on a thumb drive and mailing it to its destination.

Redfern says there’s no reason why high-speed fiber-optic internet can’t be brought to Nunavut. She points out that Quintillion is building fiber-optic internet connections to northern Alaskan cities, with a plan to eventually reach Canada’s eastern Arctic. Greenland’s capital of Nuuk, just across the Davis Strait from Iqaluit, enjoys a high-speed fiber-optic connection, as does Svalbard off the northern coast of Norway.

Redfern has been lobbying hard to have her city become similarly connected. Arctic Deeply talked with her about how limited internet access impacts the lives of Nunavut residents.

Arctic Deeply: You’ve been vocal about the limitations of the internet in Iqaluit. Can you give us some context about exactly how slow or limited it is?

Madeleine Redfern: When it’s completely down, which happens quite regularly, then it’s completely impossible to do any internet-type activities, including being able to get money from your bank – whether it’s through the ATM or even at the teller – purchase gasoline with a credit card or debit, purchase groceries, rent a movie, pay for your meal at any of the restaurants.

We are heavily dependent, as a society, on card purchases and online or digital financial transactions. So it slows down work productivity. It’s very frustrating. We take for granted that you can send texts and that they will be read and received immediately and responded to, or emails, or social media messages. That is the reality that we’re living in.

Arctic Deeply: As a mayor, this must present special challenges to you, trying to run a city that has limited connections to the rest of the world.

Redfern: Well, it disrupts communication. The reality is that you can’t do your work if you’re not communicating – communicating amongst your colleagues, your partners or the clients that you serve. In this day and age where there’s an expectation of immediate or instantaneous responses, people are saying, “Well, I sent the email,” and they’re like “Nope, still don’t have it.” Then you check with them later and you resend it, “Nope, still don’t have it.”

Often an I.T. department will request staff to send large files or receive large files after hours, scheduling those to be done between the hours of 10 p.m. and 6 a.m. in an attempt to use the network when there’s less users on it. But that also means that we don’t effectively use products or services such as iCloud, which of course is quite often the norm. And there are still government departments or businesses or contractors who are having to send large files by thumb drives, putting a thumb drive in a bubble envelope and putting it on a plane, whether it’s from one community to another community within the territory or to the south.

I recently had to renew my subscription for Microsoft Office and I simply could not download it. After five attempts, all spread over several days, I was unable to download the application. Thankfully, I was leaving the territory a few days later and I was able to do it when I arrived in Ottawa and checked into my hotel. I was able to download the application in, I believe it was, 23 minutes.

There’s also a lot of people who are desperate to be able to do things like download podcasts, books, movies, all sorts of products that you simply can’t download here. The data caps are quite low. Their over-cap surcharges are extremely high.

Arctic Deeply: I find it so interesting that some people actually mail the thumb drives or fly the thumb drives to different cities, that that’s actually more efficient.

Redfern: Yeah. It is and it’s faster. We often are also required to actually have websites in the south to host that content, because you couldn’t have some real-time service in the North.

So even our own cultural content that we produce in Inuktitut or from Nunavut is actually more accessible to people who are living in the south or anywhere else in the world than ourselves. We have local cultural content producers in or in Iglulik, Pond Inlet, Clyde River, Arviat, and it is absurd that people outside of our own culture and our own territory have easier access to our cultural content.

There are folks that are looking at trying to figure out how this content could be kept within the community, possibly through something like an intranet, so it’s preloaded and so that you don’t have to connect to the world wide web through the satellite to access it.

Arctic Deeply: Are there any other innovative solutions or work-arounds that you and your community have found?

Redfern: There’s also been talk about putting content on the computers either at the community access program points or at college or in schools. But again, the challenge with that is that you’re talking about putting it on systems which not everyone has access to, or on systems which already have a high user demand. You go to the library here, and anytime that the cap is open, every computer is filled and people are waiting to get onto the shared computers. What ends up happening is most people just use their own systems at home and, like myself, try to watch as little video clips as possible.

It can be frustrating when you’re trying to open up even a newspaper article which is embedded with a lot of graphics and a lot of video and just going “No, I don’t want your video advertising.” You’re not always able to close down those video windows.

Arctic Deeply: You said that many other territories around you do have these fiber-optic cables to them, so why not Nunavut?

The current approach is the private-public sector model. The private sector can’t do it on its own which requires, therefore, significant public investment. We only have one member of Parliament, out of 336 members across the country.

When [infrastructure] minister [Amarjeet] Sohi was here two weeks ago, when he saw his colleague, [small business] minister [Bardish] Chagger at the Ottawa airport, his first comments to her was that he was shocked by the level of poor internet access and usability. That’s also why it’s really important to have as many federal ministers and senior bureaucrats come to the North so they can truly experience it.

Arctic Deeply: In 2011, the United Nations declared that access to the internet be a human right. You have similarly, on Twitter, equated internet access to roads, railways, postal systems, in terms of need of access. Do you feel like the internet situation in your city is bad enough that it counts as a human rights issue?

Redfern: I think it’s an essential service and it’s a fundamental piece of infrastructure that is absolutely required to govern, manage and administer, but it’s also essential in the sense of being able to respond to emergencies. It’s essential for the transportation and aviation sector. It’s essential for the shipping companies. It’s essential for the military. It’s essential for Arctic research. It’s an essential part of doing business.

When the satellite went down in October, 2011, the whole northern part of Canada literally went black. What I mean by that is that there was no telecommunications in and out of the region. Flights were grounded. No one was able to do any communications internally or with the outside world. We were completely and utterly cut off. If an emergency happens when there’s a total blackout, you’re talking about lives are at risk.