Ellesmere Island, one of the northernmost landmasses on Earth, is part of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago.

Known for its remote and extreme environment, the island has been significant in Indigenous history, scientific research, and Arctic exploration.

Geography and Climate

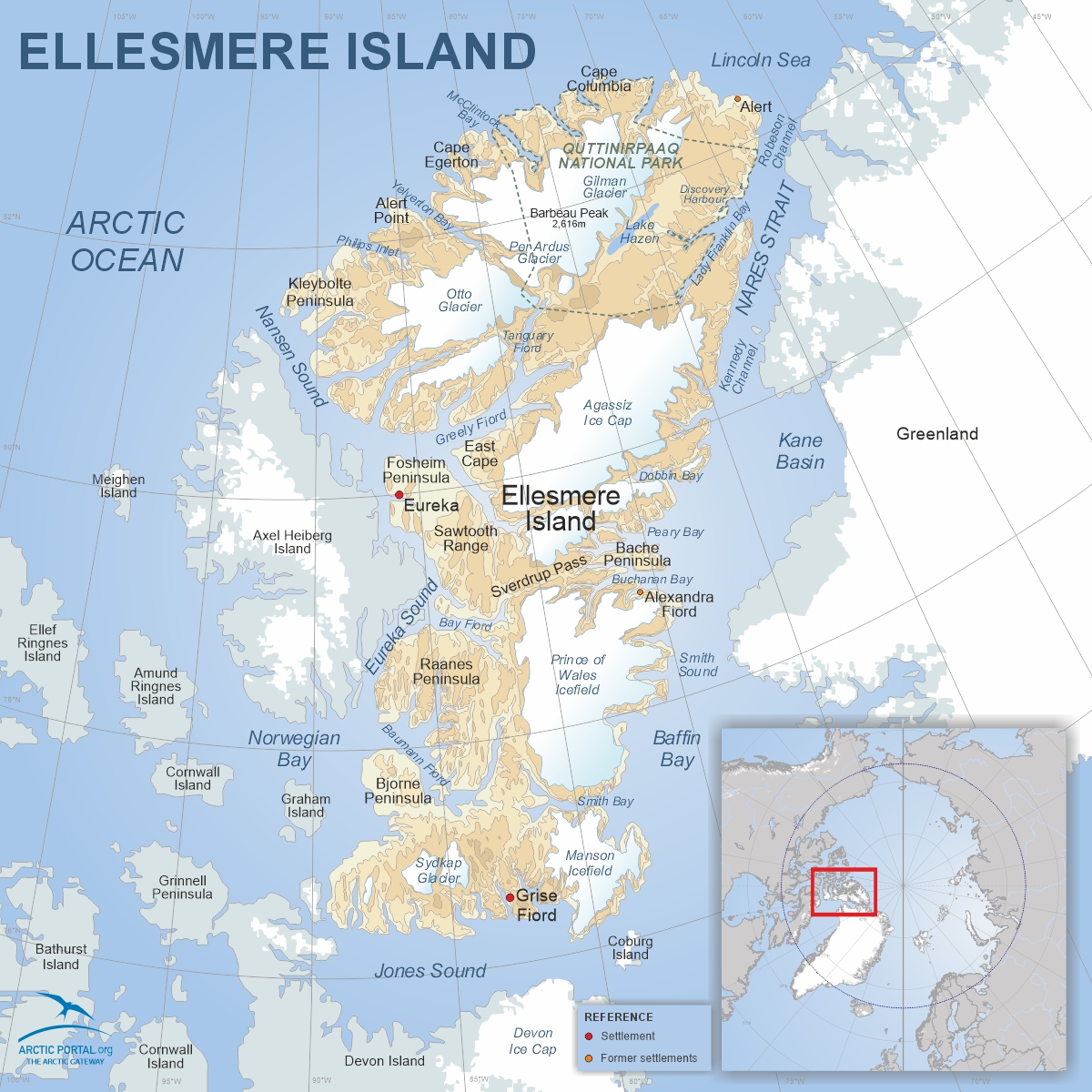

Ellesmere Island, the third-largest island in Canada and the tenth-largest in the world, is characterized by ice-covered mountains, deep fjords, and expansive ice shelves. It stretches approximately 830 kilometers (520 miles) in length and 645 kilometers (400 miles) in width, covering an area of about 196,235 square kilometers (75,767 square miles). Barbeau Peak, the island’s highest mountain and the highest point in Nunavut, rises to 2,616 meters (8,583 feet).

Approximately 40% of Ellesmere Island is covered by glaciers, making it one of the most heavily glaciated areas in the Canadian Arctic. The island's climate is characterized by its extreme Arctic conditions, including vast tundra landscapes, desert-like dryness, and minimal precipitation, making it one of the driest places in the Arctic. With long, harsh winters and brief, cool summers, Ellesmere Island remains icebound for much of the year. Despite the challenging environment, the island supports a variety of life forms that have adapted to its unique ecological conditions.

The harsh climate limits the diversity of plant life, yet Ellesmere Island hosts a range of specially adapted Arctic flora. Notable species include purple saxifrage and Arctic poppy, which bloom during the short summer season. Cushion plants, lichens, and mosses are widespread, covering the tundra and rocky outcrops. One of the few woody plants present is the Arctic willow (Salix arctica), a dwarf shrub that hugs the ground to withstand freezing winds. There are no true trees on Ellesmere Island due to the extreme cold and permafrost, as the island lies well north of the Arctic tree line.

The park is renowned for its extensive glaciers and ice caps, which contribute to the island’s rugged topography. The harsh desert-like conditions and minimal precipitation are reflective of the larger island's environment. Despite these extreme conditions, Quttinirpaaq supports a fragile ecosystem with uniquely adapted flora and fauna, including Arctic wolves, muskoxen, and Arctic hares. Due to its extreme isolation, only about 50 people visit the park each year, making it one of the least-visited national parks in the world.

Discovery and Early Exploration

Ellesmere Island was first sighted by the English explorer William Baffin in 1616, but its harsh and remote conditions meant it remained largely uncharted for centuries. The first significant exploration came in 1818 when John Ross mapped parts of its coastline while searching for the Northwest Passage. The island received its name during the 1852 expedition led by Sir Edward Inglefield, in honor of Francis Egerton, 1st Earl of Ellesmere, who was the president of the Royal Geographical Society from 1849 to 1852. Later, in 1875–76, Sir George Nares led an extensive scientific and geographic survey of the region, furthering knowledge of the Arctic.

As part of the First International Polar Year, the American explorer Adolphus W. Greely led an expedition (1881–1884) called the Lady Franklin Bay expedition, that extensively explored northern Ellesmere Island from their base at Discovery Harbour. However, the mission turned tragic when supply ships failed to arrive, leading to the deaths of most expedition members; only seven out of 25 survived.

Much of the island's mapping and exploration were driven by the quest for the North Pole. Between 1898 and 1902, Norwegian explorer Otto Sverdrup mapped several nearby islands while surveying Ellesmere. In the early 20th century, the Canadian government sought to reinforce its Arctic sovereignty by dispatching Albert P. Low in 1903–04. He placed a cairn marking Canada's claim and hoisted the national flag at one of the island’s northernmost points.

There are also intriguing suggestions that Norse explorers may have reached the High Arctic centuries earlier. Norse sagas and archaeological hints imply that Viking voyagers explored regions as far west as Ellesmere Island, particularly the Smith Sound area, around 1250 AD. While conclusive evidence remains elusive, these accounts contribute to the island’s mystique and suggest that the Arctic may have been part of broader Norse exploration routes.

Historical Significance

Beyond its role in early exploration, Ellesmere Island has held strategic and scientific significance throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Its remote northern location made it an ideal site for asserting Canadian Arctic sovereignty, particularly during the early 1900s when efforts were made to solidify a national presence in the High Arctic.

During the Cold War, the island’s geographic proximity to the North Pole led to the establishment of weather stations and military outposts such as Alert, the northernmost permanently inhabited place in the world. These installations served both defense and research purposes, monitoring atmospheric conditions and facilitating emergency preparedness during a time of heightened geopolitical tension.

Ellesmere Island has also become an important location for scientific research, particularly in the fields of glaciology, climate science, and Arctic ecology. The island’s relatively untouched environment provides unique opportunities to study ancient ice formations, permafrost, and ecosystem responses to climate change. Long-term environmental monitoring in this region contributes valuable data to global climate models and helps researchers understand the pace and consequences of warming in polar regions.

Indigenous Presence

Indigenous Presence

Long before European explorers arrived, the Inuit inhabited and navigated these icy landscapes, relying on their deep understanding of the Arctic environment for survival. The island has been home to successive cultures of Indigenous peoples for thousands of years. The earliest known inhabitants were the Pre-Thule (Pre-Inuit) groups who arrived around 4,500 years ago, followed by the Dorset culture, which thrived for centuries before being displaced by the Thule people, ancestors of the modern Inuit, around 1,000 years ago.

These early Arctic settlers developed specialized hunting techniques, relying on seals, muskoxen, and other wildlife for food, clothing, and materials. Archaeological discoveries on Ellesmere Island provide valuable insight into these past cultures. Artifacts found on the island include small, finely made stone tools associated with the Arctic Small Tool tradition, as well as artistic carvings from the late Dorset period. The Thule people, who arrived in the late 12th century from the Bering Sea, left behind the remains of settlements along fjords and islands where they hunted sea mammals, including large bowhead whales. Evidence also suggests possible contact between Thule Inuit and Norse voyagers around 1250 AD in the Smith Sound region. However, Ellesmere Island was eventually abandoned by the Inuit during the Little Ice Age, between 1650 and 1850 AD.

While permanent settlements on Ellesmere Island today are sparse, Inuit communities in Nunavut maintain strong cultural and historical ties to the land, preserving traditional knowledge and practices that continue to be passed down through generations.

Settlements on Ellesmere Island

Settlements on Ellesmere Island

Though largely uninhabited today, population in 2024 according to the World Population Review was 144. The island has a few settlements and research stations.

Grise Fiord, the northernmost civilian settlement in Canada, is located on the southern coast of the island. It was established in 1953 as part of a government relocation program and is home to an Inuit community that has adapted to the extreme Arctic conditions. It has a population of approximately 130 people, making it one of the smallest and most isolated communities in Canada.

Eureka, a research station founded in 1947, is known for its meteorological and climate research. Scientists conduct studies on atmospheric conditions, climate change, and Arctic ecosystems. With a small year-round staff of about 8 to 10 people, it operates one of the world’s most northerly weather stations. The population temporarily increases during the summer months when additional researchers arrive. (photo of Eureka)

Alert, situated at the northern tip of the island, is the northernmost permanently inhabited place on Earth. Established as a military and signals intelligence base, it also plays a key role in scientific research and weather monitoring. Its population fluctuates and can be between 50 and 60 personnel, primarily military and scientific staff.

Alexandra Fiord, once a Royal Canadian Mounted Police post, is now primarily used as a seasonal research base for studying Arctic ecology and climate change. Unlike the other settlements, it does not have a permanent population but hosts small groups of researchers and scientists during warmer months.

Wildlife of Ellesmere Island

Wildlife of Ellesmere Island

Ellesmere Island hosts a diverse range of Arctic wildlife, uniquely adapted to its harsh climate. Some of the most notable species include:

Mammals: Polar bears, Arctic wolves, Arctic foxes, muskoxen, and Arctic hares are among the key land-dwelling species. The Arctic wolf, a subspecies of the gray wolf, is a particularly notable predator on the island, preying on muskoxen and Arctic hares. The muskox, in particular, is one of the island’s most iconic inhabitants, using its thick coat to endure the extreme cold.

Marine Life: The surrounding waters are home to seals, walruses, and several whale species, including narwhals and belugas. These marine mammals rely on the region’s ice and open water to survive.

Birds: Ellesmere Island provides crucial breeding grounds for Arctic birds such as the snowy owl, gyrfalcon, and various species of gulls and geese. During the brief summer season, migratory birds arrive to nest and raise their young.

Insects and Flora: Despite the extreme conditions, resilient Arctic flora such as mosses, lichens, and dwarf willows grow during the short summer. Additionally, insects like midges and Arctic bumblebees contribute to the fragile ecosystem. There are also thirteen known species of spiders inhabiting the island, demonstrating the surprising biodiversity of even the harshest Arctic environments.

Climate Change and Environmental Impact

Ellesmere Island is at the forefront of Arctic climate change. Its once-stable ice shelves, such as the Milne Ice Shelf, formerly one of the last intact shelves in the Arctic, have dramatically receded or collapsed in recent years. Rising temperatures are also altering permafrost conditions and impacting ecosystems and wildlife, including polar bears, muskoxen, and Arctic foxes. As a rapidly changing environment, the region has become a critical indicator of global climate trends, attracting scientists from around the world.

Conclusion

Ellesmere Island remains one of the last great frontiers on Earth, offering invaluable insights into Arctic history, indigenous resilience, climate change, and scientific discovery. As the Arctic continues to warm, the island’s significance as a research hub and a symbol of wilderness preservation will only grow, making it a focal point for both environmentalists and policymakers in the years to come.

An article written by Fanney Sigrún Ingvadóttir

Source: Britannica, The Canadian Encyclopedia, NASA

Map: Arctic Portal