Construction workers at an Alaskan oil construction project had just finished building the ice road connecting their land-based operations to a nearby island when a worker made a discovery that would bring them to a halt for days. There, on the edge of the manmade island not too far from where the road entered, was a polar bear. This wasn't just any polar bear. There, in the Beaufort Sea close to an oil industry drilling project, appeared a mother bear and her cub.

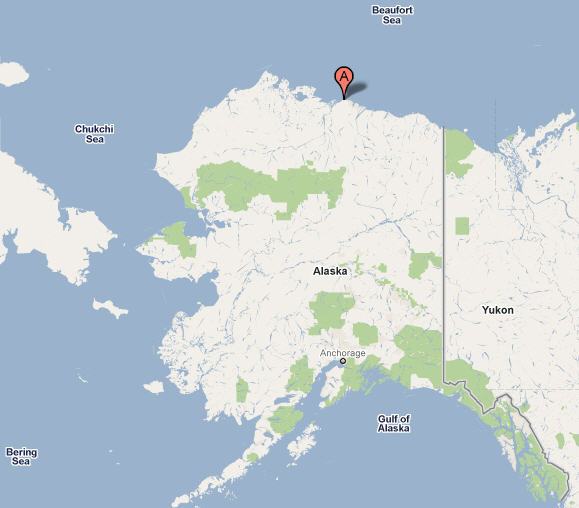

The Alaska´s newest oil producer, ENI, just brought online earlier this year its shore-based Oliktok Point drilling operation, which sits east of Barrow along Alaska's north slope close to Prudhoe Bay. Work at the nearby island, known as the Spy Island Development site, was under way to prepare the manmade island for drilling that's expected to begin this fall. But the discovery of the polar bear den triggered an immediate pause that only the bear's departure could lift.

Activities at the island could resume as early as Wednesday evening provided the bears, which haven't been seen for at least two days, do not resurface.

Bruce Woods at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife service says It's rare for a bear sighting and den to force a shut-down of work altogether.

It's not uncommon for industry to run across polar bears, and avoidance rules are in place to help minimize the impacts to the animals and the danger they may pose to humans. Roads may have to be rerouted and people may have to change the routes they take. When an inhabited den is discovered, a one mile quiet zone must be established around the site, states Tom Evans, a polar bear biologist with the USFWS Anchorage office. Due to this, all operations are ceased until the bears are gone from the den site.

In the two decades that Evans has worked for the service, he has heard of a bear den forcing work to stop only a handful of times.

After ENI's employees immediately stopped what they were doing and made the call about the Spy Island bears, biologists from Evans' office traveled to the site to monitor the situation. They set up cameras and used an infrared scope to measure whether any heat was present.

This particular mother bear apparently made her winter home by burrowing into a snowdrift that had formed along a series of large gravel sacks on the perimeter of the island that are used to help protect it from ice and erosion. It's thought that by Monday, three days after the bears were first seen, that the duo had moved on. Biologists followed tracks leading away from the site for several miles and never found evidence that the bear had circled or turned back. It's likely, Evans said, that she headed off in search of seals to eat. With a young cub, though, she's not likely to try to do much deep water swimming and will probably stay on the ice pack that's still connected to the shore rather than venture out to the southward-floating pack ice, Evans said.

The biologists monitoring the bears didn't personally witness their departure, but workers apparently saw the bears leaving the area on Sunday, according to Evans. And, he said, the scientists haven't had time to review their surveillance footage to find out if they captured any images of the bears.

Biologists are aware of two other dens in the same region -- one on Howe Island, and another on a section of gravel along the coastline known as the "staging pad" -- but neither have impacted industry operations.

Bears typically make their dens in November. Cubs are born in January, and mid-March to mid-April is generally when they start to emerge, and a mother bear's hunger level will determine how much time she spends with her cub hanging around the den. Sometimes, bears will wait up to two weeks before moving on, he said.

ENI Petroleum, headquartered in Italy, was unable to immediately respond to questions about the bear sighting or the shutdown of its construction operations, according to Hans Niedig, the company's Anchorage-based government and external affairs manager, citing the company's formal protocol for receiving and responding to questions from the press.

Provided the bears don't show up again, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service had planned to let ENI resume operations at Spy Island.

Everybody did the right thing, Woods said, which resulted in a good outcome. "There was no harm to anybody, and no harm to the bears," he said.

Pictures: