Increased monitoring of Arctic weather conditions could help predict big storms that strike more southerly latitudes, according to new research by the National Institute of Polar Research in Japan.

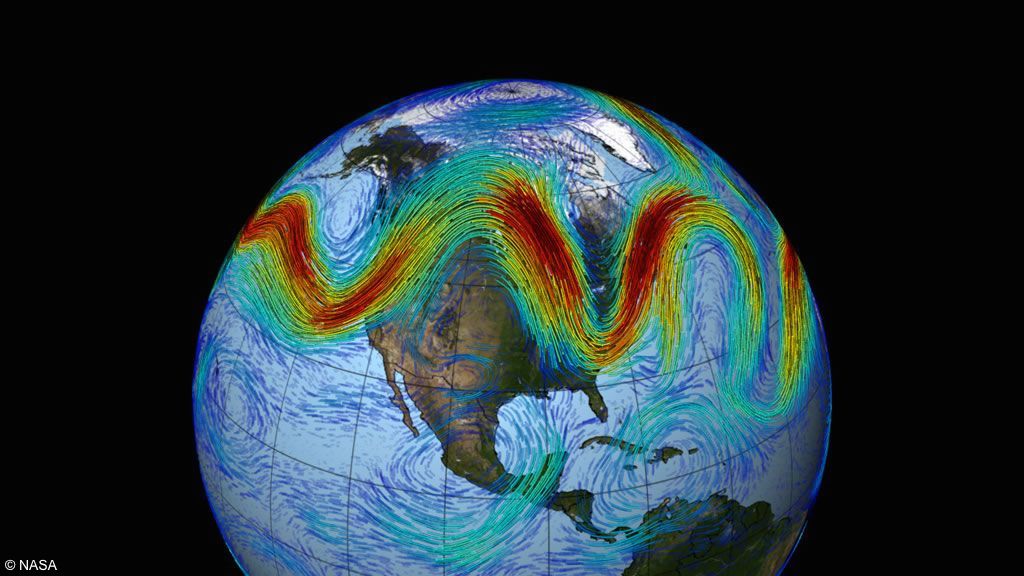

During the second week of February in 2015, the meandering jet stream slipped steadily southward, pulling down icy fingers of Arctic air. In Buffalo, New York, February 15 was the coldest day in 21 years, and record daily lows were recorded from the Great Lakes across the Eastern Seaboard. Nicknamed winter storm Neptune, the blizzard halted traffic with snowfall up to two feet, and winds in excess of 80km (50 miles) per hour brought down trees.

Extreme winter weather events such as Neptune have become increasingly frequent in recent years and there is substantial evidence linking these mid-latitude storms to changing Arctic weather patterns. With their high human and socioeconomic impacts, predicting these storms could have large societal benefits.

New research, published in the Journal of Geophysical Research, shows that it may be possible to improve forecasts of these extreme events at mid-latitudes across Europe, North America and East Asia, while simultaneously enhancing local Arctic weather predictions.

“The number of observations over the Arctic region is limited due to the harsh environment,” said Kazutoshi Sato, the lead author of the paper and postdoctoral scientist at the National Institute of Polar Research in Japan. “But I think that an increase in the number of observations at existing Arctic stations will improve weather forecasts over the Northern Hemisphere.”

In an era of rapid climate change, Arctic sea ice and snow cover are melting at escalating rates. More open water has led to warmer and moister air masses over the pole, which elbows at the polar jet stream – an effect with far-reaching consequences. As the jet stream meanders southward, it tows down Arctic air, creating “cold-air outbreaks” and bringing extreme weather.

“In climate science, the emphasis has long been on the tropics, so focusing on changes in the Arctic provides an opportunity to improve seasonal forecasts,” said Judah Cohen, climate scientist and director of seasonal forecasting at Atmospheric and Environmental Research. “It’s been underappreciated in the community until recently.”

Extreme storms have been increasing in Japan, as well as North America, and a group of Japanese scientists decided to study the link in more detail, to see if they could improve forecasts with additional observations.

The scientists looked at measurements taken with weather balloons across the Arctic from Barrow, Alaska, to Bear Island in the Svalbard Archipelago, to Eureka, Nunavut. These balloons take measurements as they ascend into the stratosphere, allowing a vertical sampling of Arctic air masses.

While measurements are typically taken just twice daily, the Japanese scientists acquired data four times per day during the period leading up to winter storm Neptune. They also received additional data from a Norwegian research vessel that had been traveling north of Svalbard at the time.

Comparing the normal level of data with the additional measurements, the scientists created forecast models, which they compared to the winter storms that swept across North America and East Asia. The increase in measurements helped reduce the uncertainties in the models, which allowed them to accurately recreate the storms.

Future studies, the scientists hope, will help pinpoint precise locations for optimal observation. New stations could also improve local weather forecasts for residents in the region, including sea ice predictions for local fishermen and shippers crossing the Northern Sea Route.

Due to the remote locations, logistics and lack of funding make it financially unfeasible to create new stations. However, increasing the number of daily recordings at existing stations isn’t out of the question. And if the Northern Sea Route sees an increase in traffic, commercial ships passing through could also take on a secondary job as mobile weather stations, taking pressure, wind and temperature measurements from the surface.

“Japan alone cannot manage the Arctic operational observations,” said Jun Inoue, coauthor on the paper and associate professor at the National Institute of Polar Research in Japan. “However, we can demonstrate the importance of the observations to the stakeholders.”

Improvements to observations seem to be on the horizon. The Year of Polar Prediction – a project by the World Meteorological Organization scheduled to launch later this year – aims to support research to further develop prediction services, including intensified observations needed to improve forecasting methods.

This article originally appeared on Arctic Deeply.