In Arctic Policies of the Nordic Countries, published in The New Nordic Lexicon on September 17, 2024, author Kat Hodgson examines how Arctic policies offer a window into the pressing global issues of our time, as well as the unique dynamics within the Nordic and Arctic regions.

These policies reflect both domestic and international priorities, highlighting distinct national characteristics while underscoring common themes such as security, environmental stewardship, Indigenous rights, and the challenges of depopulation.

At the end of her article, Hodgson provides links to a selection of Arctic policies, many of which can be found on our website, ArcticPortal.org, offering readers an accessible resource to delve deeper into these influential documents shaping the Arctic’s future.

Discover the complete article below by the author Kat Hodgson, please note that the images differ from those in the original publication.

Arctic Policies of the Nordic Countries

Approaches to the Arctic reveal wider geopolitical trends as well as the Nordic countries' domestic concerns.

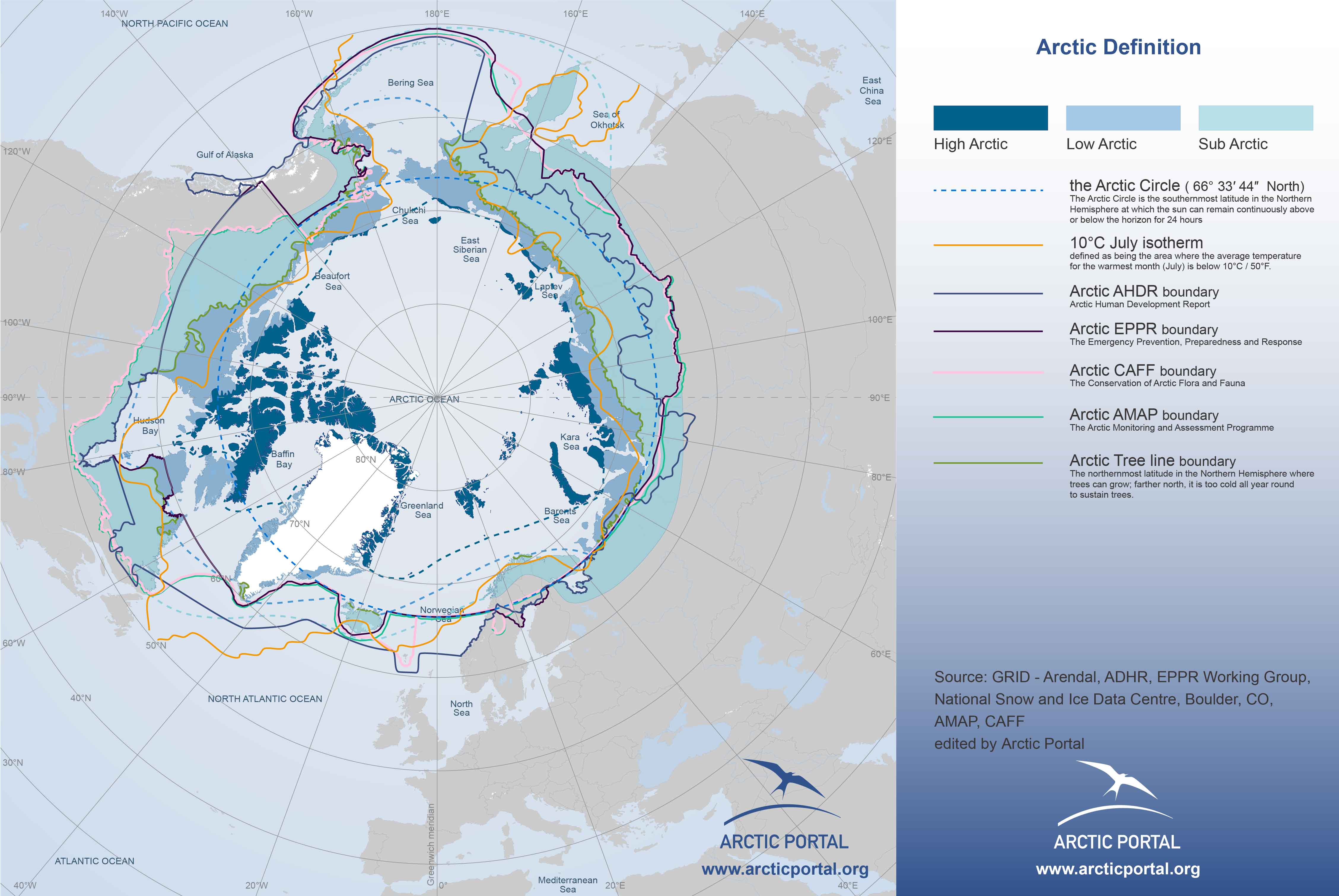

“The Arctic” can be defined differently, but the definition provided by the 2004 Arctic Human Development Report is most commonly used because it takes into consideration cultural, historical, and political boundaries:

“The Arctic” can be defined differently, but the definition provided by the 2004 Arctic Human Development Report is most commonly used because it takes into consideration cultural, historical, and political boundaries:

“all of Alaska, Canada North of 60°N together with northern Quebec and Labrador, all of Greenland, the Faroe Islands, and Iceland, and the northernmost counties of Norway, Sweden and Finland... [and in Russia,] the Murmansk Oblast, the Nenets, YamaloNenets, Taimyr, and Chukotka autonomus okrugs, Vorkuta City in the Komi Republic, Norilsk and Igarka in Krasnoyarsky Kray, and those parts of the Sakha Republic whose boundaries lie closest to the Arctic Circle” (pp. 17-18)

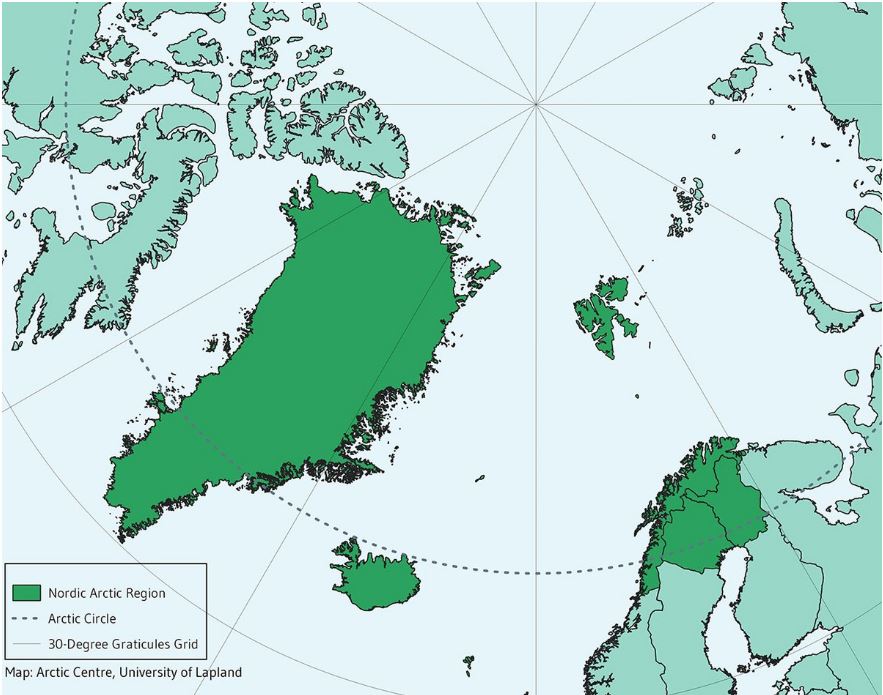

All five of the Nordic countries have territory in the Arctic, sit on the Arctic Council, and have issued Arctic policies at various points in time (see the end of the article for a list with links). The eight Arctic countries include all of the five Nordic countries as well as the Russian Federation, the United States and Canada. Denmark is considered an Arctic country because both the autonomous territories of Greenland and the Faroe Islands being part of the Danish realm. Greenland and the Faroe Islands have issued their own Arctic policies, as have two indigenous people's organisations (Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) and the Saami Council), but the main focus of this article is the Arctic policies of the five Nordic states.

The importance of the Arctic

According to the Norwegian Polar Institute, the Arctic is warming three times faster than the global average, resulting in more rapid and more extreme effects for land, water, ice, animals, and humans in the region. All of the Nordic states' Arctic policies address the fact that climate is affecting their Arctic territories and acknowledge the hazards, risks, and threats that climate change can do - or is already doing - to the environment. But these countries also see opportunities for development in this change. One of the biggest benefits of a warmer Arctic with less sea ice is that it opens new routes for marine shipping – particularly the Northwest Passage over North America and the Northern Sea Route over Russia. It also holds prospects for expanding natural resource exploitation, including hydrocarbons, minerals, and fish.

The warming Arctic has also created increasing global interest in the region, which subsequently presents further challenges for security and indigenous peoples. However, what “security” and “development” mean are different to each state.

Security: A focus on defensive security

Security: A focus on defensive security

In political science, security has traditionally referred to a country’s ability to protect its territory, people, and interests against other countries, commonly involving military capabilities. While all the Nordic countries’ Arctic policies refer to this understanding of security, the focus is primarily on defensive security (the ability to protect the homeland; as opposed to offensive security, which involves the ability to attack other countries).

All of the Nordic Arctic policies emphasise the importance of international cooperation, particularly through the Arctic Council. However, they also state that Russia, in particular, has been seen as a security threat. All of the policies (excluding Greenland and the Faroe Islands) were written prior to Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, which compelled Sweden and Finland to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). The fact that, now, all of the Arctic countries, except Russia, are NATO members is not yet reflected in the Arctic policies of the Nordic countries.

Beyond traditional security concerns, other understandings of security arise. Finland's policy focuses more on internal security, meaning the assurance of safety and wellbeing for people through capable search-and-rescue services and civil preparedness by the police and border guard. It also promotes human security, a type of security focusing on people instead of countries; the idea is that every human on earth deserves to live a secure and dignified life, free from fear and want.

Greenland's policy focuses on strengthening civil preparedness and makes explicit mention of concerns about cyber security. Moreover, because it is working toward independence, a priority for Greenland is the creation of a self-sustaining economy; therefore, its policy has a specific focus on economic or “supply chain” security to guarantee residents' access to food, medicine and fuel (p. 23).

Environment: Lip service or empty pledges?

In their policies, Norway, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, and Greenland note the opportunities for increased shipping, tourism, and fishing in high northern waters. However, as Iceland’s policy notes, this can also lead to an increase in pollution (p. 5). The major pollution risks it lists are oil leaks or spills, the release of toxic substances into both the air and water, radioactive materials, and plastic waste. Pollution also endangers the cultural foundations of these societies that live off the ocean’s resources.

Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Iceland mention their commitments to the Paris Agreement and their goals to all be low-carbon or carbon neutral by mid-century. Paradoxically, they all also stress the need for development in their Arctic regions. However, all (except Greenland) invoke the concept of sustainable development in connection with this. The heart of the “sustainable development” concept involves striking a balance between three “pillars” of development: environmental, social, and economic. However, numerous critics have pointed out that, since its introduction in the 1980s, the concept has been co-opted by governments and businesses to the point that it is now an “empty signifier” (meaningless) and/or a cover for greenwashing and continued colonialism.

This criticism can be applied to several Arctic policies. Norway, Iceland, the Faroe Islands and Greenland barely mention the environmental and social pillars of sustainable development; they focus almost exclusively on economic development. Norway states the importance of oil and gas to the national economy, and indeed has continued to expand its oil exploration activities, leading to accusatios of hypocrisy by environmental groups. Even Finland seems to allude to this in its Arctic policy, stating that “the opening up of new fossil reserves in Arctic conditions is incompatible with attaining the targets of the Paris Agreement” (p. 26).

Although Denmark is a party to the Paris Agreement, the Faroe Islands and Greenland are not. Nonetheless, the Greenland has stated its intention to become a party to the Agreement (p. 15). However, Greenland also states that it is agreeable to developing (unsustainable) mining operations because the minerals would be used to produce “renewable sources of energy, thereby doing its part to lower CO2 emissions on a global scale” (p. 15).

The Arctic policies of Finland and Sweden appear to be the most balanced, as they spell out all three pillars in their development descriptions and advocate the creation of a circular economy. Finland also supports the Just Transition model, which means that “emissions reduction and adaptation measures are carried out in a way that is fair from the social and regional perspective and involves all sectors of society” (p. 31). Its policy even states that “Nature not only has intrinsic value but…also helps to improve human health and mental well-being” (p. 29).

Indigenous peoples: "The Arctic is our home"

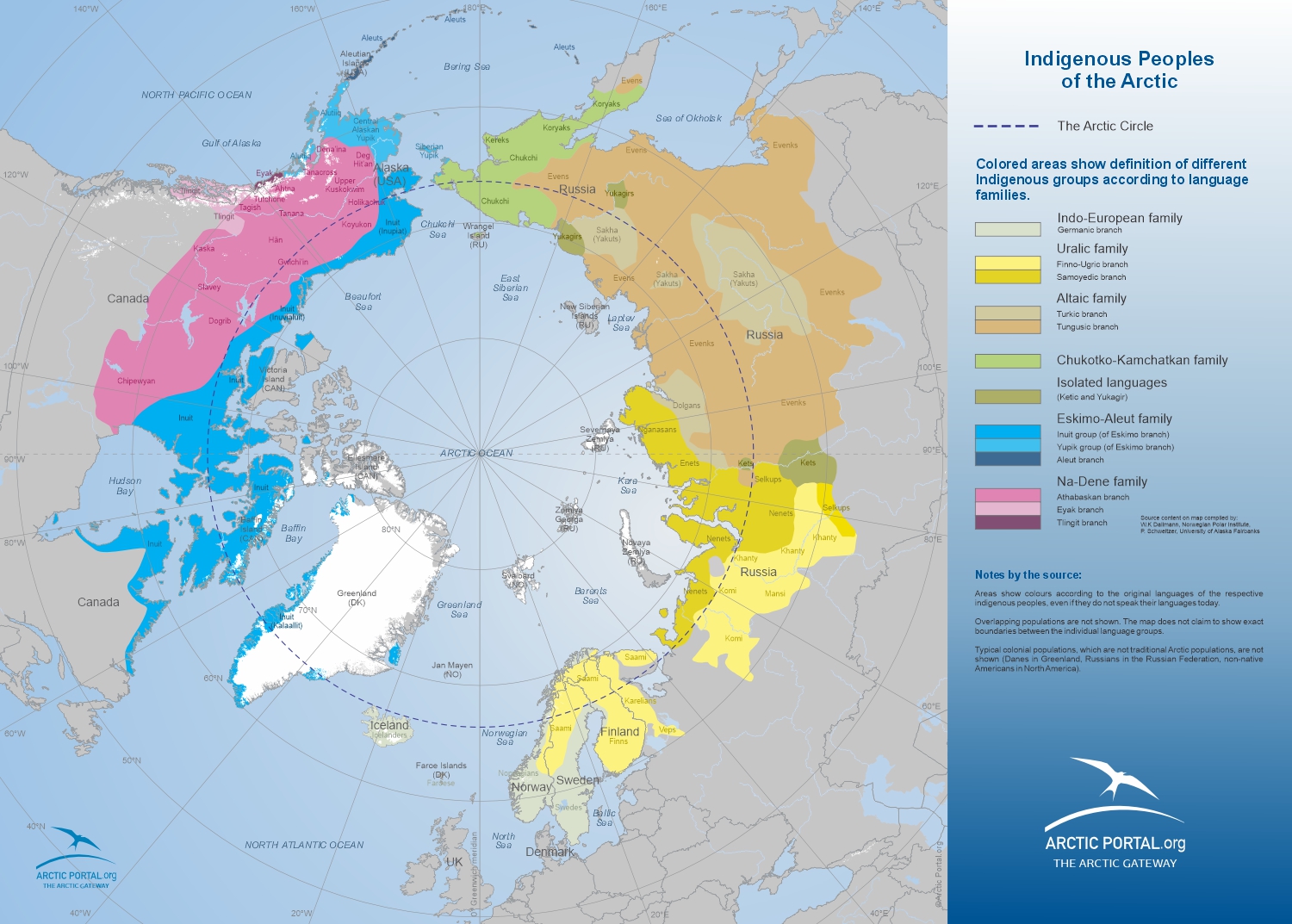

In addition to the nationalities after whom the countries are named (Danes, Finns, Icelanders, Norwegians, and Swedes), the Arctic is home to two transnational Indigenous groups that are also connected with the Nordic countries—the Inuit and the Sámi.

In addition to the nationalities after whom the countries are named (Danes, Finns, Icelanders, Norwegians, and Swedes), the Arctic is home to two transnational Indigenous groups that are also connected with the Nordic countries—the Inuit and the Sámi.

Sápmi, the ancestral homeland of the Indigenous Sámi people, extends across the territorial boundaries of all Norway, Sweden and Finland, as well parts of Russia. Despite having the largest Sámi population, Norway’s Arctic policy devotes the least attention to Sámi relations and issues, focusing primarily on engaging in consultations with the Sámediggi (Norwegian Sámi parliament) and with reindeer herders. Sweden offers deeper consideration of Sámi issues by including the contributions that Indigenous traditional knowledge can offer to scientific research with its intention to “encourage exchanges of knowledge between researchers and Indigenous peoples in the Arctic and to work to make traditional knowledge and scientific research mutually available” (p.37). Finland dedicates a section of its Arctic policy specifically to the rights of Sámi as Indigenous people and places even more detailed emphasis on the social wellbeing of its Sámi population, including the need to ensure that educational and health services are available in the Sámi languages and are culturally sensitive to their “special needs” (p.36). Like Sweden, it aims to include traditional knowledge into climate research and policymaking; it even proposes the creation of a Sámi Climate Council.

Greenland’s policy stands out for its emphatic use of decolonial language, such as “All relations are based on the premise that Greenland and the Greenlandic people constitute an independent people and nation” (p. 7). The content and language of its policy make clear that Greenland intends to use its right to self-determination to strengthen ties with its North American neighbors as well as Iceland. It also states its intense desire to “break away from centuries of colonial trading structures” (27) and create direct trade opportunities with North America and Asia.

Another interesting feature of both Greenland’s and the Faroe islands’ policies is the use of “we” instead of “they” to refer to its Arctic population, whereas the other Nordic policies use “they”.

The Sámi and Inuit peoples have transnational representation through the Saami Council and Inuit Circumpolar Council and both organisations have issued their own Arctic policies. The Indigenous Arctic policies strike a different tone from their state counterparts, particularly as most of their goals revolve around the necessity of including Inuit and Sámi voices in national and international decisions involving their ancestral homelands.

Language also plays a role in the recognition of indigenous people’s rights and it is worth noting that Finland’s Arctic policy is not only published in Finnish, Swedish, and English, but also three of the Sámi languages recognized in Finland (North, Inari, and Skolt Sámi).

Residents and communities: How to attract young people?

A theme of concern for Sweden, Finland, and Norway is population decline in the north. As Sweden notes, “Many parts of the Arctic region have…an ageing population and the out-migration of young people, especially young women, who leave the region to study or work in larger urban areas further south” (p. 54). Finland also expresses concern about the gender imbalance. Norway takes seriously the desire to keep young people in the north; the Norwegian Government even consulted with a youth panel when drafting its Arctic policy and produced a paper titled An Arctic policy for young people. Each of their policies, therefore, discusses measures to improve quality-of-life conditions that would entice people to stay or move to the Arctic. Norway’s solutions take a business-friendly approach, including the establishment of investment funds, the creation of “future-oriented jobs” (p. 2), and “[p]romoting and supporting the development of a diverse cultural and sports sector” (p. 9). Both Sweden’s and Finland’s policies are notable for their encouragement of education and research in the north.

The original article provides links to a selection of Arctic Policies

About the author Kat Hodgson

Kara (Kat) Hodgson is a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Government at the University of Bergen. Her areas of interest include Arctic politics and governance, Indigenous issues, language, and gender. She received her PhD from UiT-The Arctic University of Norway. One of Kat’s big goals in life is to cross the Arctic Circle in all eight of the circumpolar countries (so far, she has done it in four of them).

Source: The New Nordic Lexicon

View Arctic Portal´s Arctic Policies Database

View Arctic Portal´s collection of International Agreements

View the Arctic Portal´s comprehensive information on Arctic Cooperation