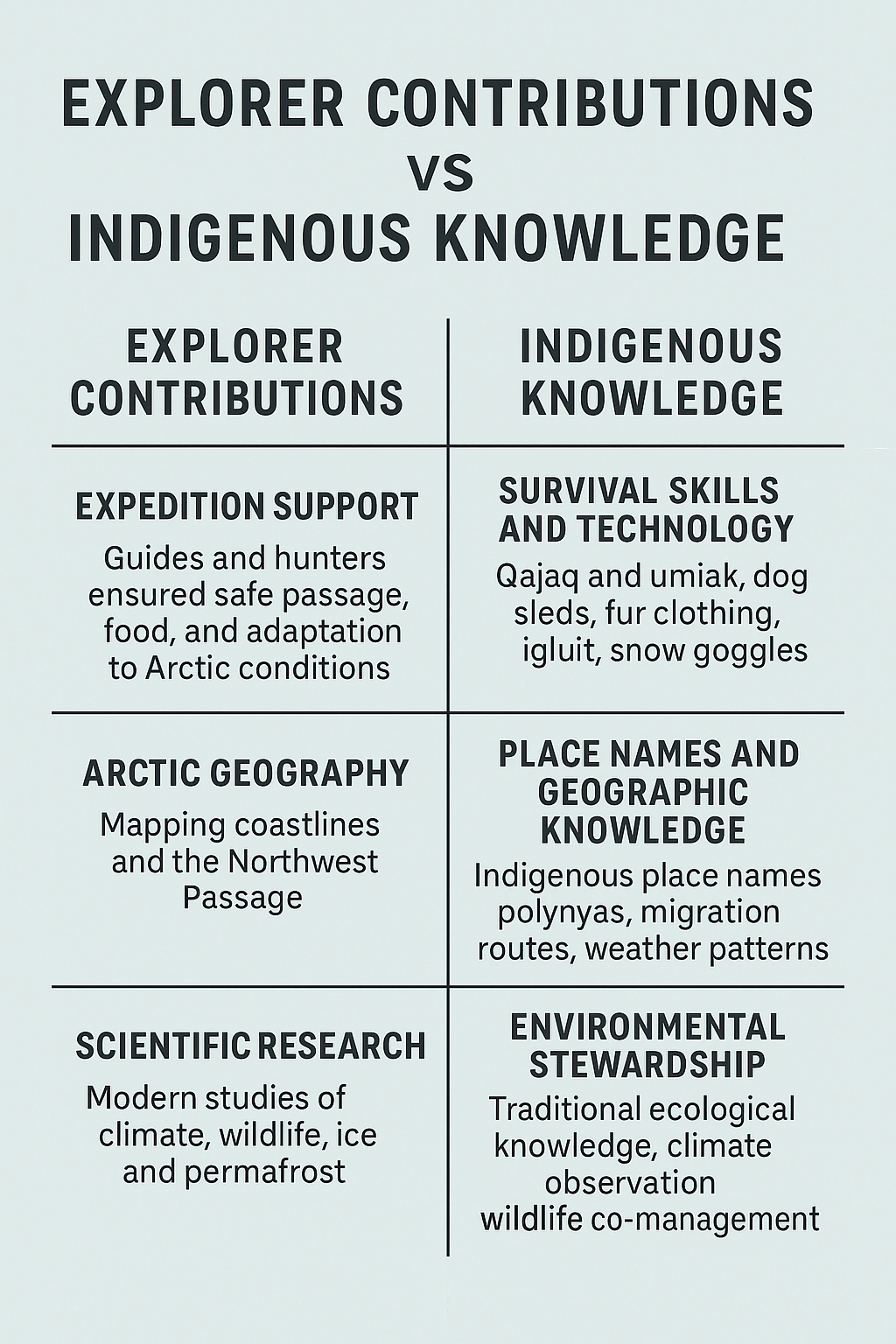

While European and North American explorers are often celebrated in the history of Arctic exploration, it was—and still is—the Indigenous peoples of the Arctic who made survival in this harsh environment possible. Their traditional knowledge, skills, and guidance were instrumental to many expeditions and remain crucial in today’s scientific research and environmental monitoring.

While European and North American explorers are often celebrated in the history of Arctic exploration, it was—and still is—the Indigenous peoples of the Arctic who made survival in this harsh environment possible. Their traditional knowledge, skills, and guidance were instrumental to many expeditions and remain crucial in today’s scientific research and environmental monitoring.

Survival Skills and Technology

Indigenous groups such as the Inuit, Sámi, Chukchi, and Yupik developed technologies perfectly adapted to the Arctic environment long before outsiders arrived:

- Qajaq (Kayak) and Umiak for navigating icy waters.

- Dog sleds (qamutiit) for transportation across ice and snow.

- Clothing made from animal skins and fur for warmth and mobility in extreme cold.

- Snow goggles, made of bone or wood with narrow slits to prevent snow blindness—an early form of sunglasses.

These innovations were often adopted by explorers who otherwise would not have survived the Arctic’s severe conditions.

Guides, Hunters, and Teachers

Many expeditions would have failed without the expertise of Indigenous guides, hunters, and interpreters:

Ipiirvik (Ebierbing), an Inuk guide, played a critical role in Charles Francis Hall’s 19th century expeditions. He was born near Cumberland Sound, Nunavut. Known for his navigation, hunting, and survival skills, which were critical to Hall´s success. He and his wife Taqulittuq were the best-known and most widely-travelled Inuit in the 1860s and 1870s.

Minik Wallace, a young Inughuit boy from northern Greenland, was brought to New York by Robert Peary in 1897. Though not a traditional explorer, his life symbolizes the complex and often exploitative relationships between Indigenous peoples and explorers. Minik later returned to Greenland but did found it difficult to reintegrate into Inuit life and later returned to the United States. Minik died during the influenza pandemic of 1918, at around 28 years old.

Indigenous families often accompanied explorers, helping them learn how to build igluit (snow houses), hunt, and travel safely over sea ice.

Place Names and Environmental Knowledge

Indigenous peoples named landscapes long before they were mapped by outsiders. Many place names now used internationally come from Indigenous languages and reflect important geographic and ecological knowledge. This includes:

- Locations of polynyas (areas of open water in sea ice).

- Migration routes of animals.

- Seasonal variations in weather and sea ice patterns.

This knowledge has been passed down through generations and is increasingly recognized in contemporary Arctic research.

Today’s Role in Science and Stewardship

Today, Indigenous communities are key partners in:

- Climate change research (e.g. monitoring permafrost thaw, ice conditions, and species migration).

- Co-management of wildlife (e.g. narwhal, caribou, polar bear).

- Community-based monitoring programs and citizen science initiatives.

- Environmental stewardship through traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), which complements modern scientific methods.